Context and AI

Whether it’s a neatly written email, a summarised report or a translated policy, most people have now seen an AI produce something impressive in seconds. But anyone who has used these systems for more than a quick demo also knows the frustration as that quality drifts. As conversations get longer, answers drift off-topic, important details get lost, or the AI confidently produces something completely wrong (hallucinations). These failures aren’t random; they’re symptoms of how the system handles (or mishandles) context.

Context is everything an AI “sees” before it generates a response:

- The prompt you typed

- The conversation so far

- Relevant documents

- The tools it uses

- Invisible system instructions

Large language models (LLMs) are often described as having a “context ” — the maximum number of tokens they can read before producing an answer. But a bigger window does not guarantee better results.

Research has shown that LLM performance typically degrades well before the context window limit is reached. In a study by Liu et (2023), performance on tasks like question answering and summarisation began to decline after only a few thousand tokens, despite models supporting far larger window sizes. This degradation arises from attention dilution and loss of signal clarity across extended contexts (Liu et al., ).

Databricks’ benchmarking of long-context retrieval in Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) systems notes a similar performance drop-off, where relevant information buried deep in a long context is routinely missed or ignored (Databricks, ). In fact, quality tends to degrade as the window grows. The model begins to blur or forget earlier details, or to overweight irrelevant information. Just as humans struggle to juggle too many facts in working memory, LLMs lose precision when context is not deliberately managed.

This is why context engineering has emerged as a critical discipline.

Context engineering

Prompt engineering crafts the words at the point of interaction. Context engineering designs the environment around it — the information, tools and structure that determine how effectively the model can act.

If prompt engineering is giving instructions to another person, context engineering is building their office, filing system, productivity tools and reference library so they can work effectively. For AI leaders, digital strategists and CMS practitioners alike, this shift matters because AI outputs are only as good as the context they’re given.

“…context engineering is the delicate art and science of filling the context window with just the right information for the next step.”

Memory and context design

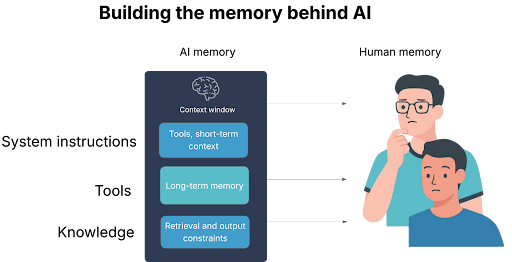

One way to grasp this is to think about human memory. We have short-term working memory — our mental “scratchpad” — and we have long-term memory, which stores knowledge and experience. Effective problem-solving in humans depends on moving information between these systems. You don’t keep every possible fact in the front of your mind at once; you retrieve what’s relevant, summarise it, and focus your working memory on the task. For humans, tool use tends to move into the subconscious. Unfortunately for AI, tool use such as Model Context (MCP) or searching online also take up space in their context.

AI systems are similar. The “context window” is like working memory: it can only hold so much at once, and performance drops when it’s overloaded. Long-term memory is provided by external stores: databases, vector indexes, knowledge graphs. A well-engineered AI retrieves the right pieces at the right time, reformats them into a usable state, and injects them into the prompt window. It also prunes or summarises as it goes, to avoid drowning in irrelevant detail. Without this orchestration, even a powerful model behaves like a person trying to read 50 open browser tabs at once.

Consequences of poor context design

The consequences of poor context design are predictable and costly. Hallucination is the most widely known: when the model makes up plausible but false information. But there are subtler failure modes:

- Context happens when a hallucination during a session is retained within the session memory and fed back as “truth” into future interactions.

- Context occurs when the system is overloaded with so much superfluous data that it can’t focus on what matters.

- Context arises when irrelevant or ambiguous context influences the response in unintended ways.

- Context is a more serious version of context confusion and happens when different parts of the context disagree, leaving the model to guess which instruction to follow.

These aren’t just technical quirks. They can lead to misinformation, compliance breaches, security risks or costly rework. In the public sector, for example, a citizen-facing chatbot with stale or contradictory context could give incorrect policy advice, eroding trust and exposing the agency to complaints or even legal liability.

Designing against context risks

Context engineering is about designing against these risks through deliberate control over what the model sees and how it interprets it. One influential paradigm emerging from and other advanced orchestration systems, breaks this process into four core actions:

- Write – Construct system-level instructions and prompts that clearly define role, tone or output expectations.

- Select – Choose only the most relevant pieces of information for the current task, avoiding unnecessary clutter or noise.

- Compress – Summarise or condense information to preserve token budget and reduce distraction, often using model-driven summarisation.

- Isolate – Segment or constrain context inputs to prevent unrelated or conflicting information from leaking into the model’s decision-making process.

This “write, select, compress, isolate” model captures the operational essence of context engineering as practised in LangChain and other agentic frameworks, including Anthropic’s Claude Code and production-grade orchestration stacks (LangChain, ; Anthropic, ).

A growing set of techniques and patterns support these components. Retrieval augmented generation (RAG) and knowledge graphs are not new forms of long-term memory but are important features to provide long-term memory options for AI. Context compression and pruning allow AI engineers to summarise existing context, aiming to reduce token count without losing key facts.

A multi-agent approach can also help by separating context among different agents for specific tasks. This task-based context simplifies what each agent needs to know, but can increase complexity and token usage when agents exchange information. Source tagging and traceability mark where each piece of context came from, improving auditability. Patterns such as context files, like in Claude Code, give AI agents a markdown-based knowledge pack to ingest before they run. These patterns all reflect a single principle: don’t leave context to chance.

Context engineering: real-world examples

The impact of context engineering becomes clear in practical examples. Imagine a policy advice bot for a government department. Without context engineering, it might attempt to answer from its general training data resulting in a mix of current and outdated policies with generic explanations. With context engineering, the bot could instead be fed the current version of the agency’s policy manuals, with each section tagged by relevance as well as access to tools to verify or access relevant, up-to-date linked content. It retrieves the right section when a citizen asks a question, summarises it to fit the prompt window, and answers with up-to-date, compliant information. Or take a customer service AI for a utilities provider. Without context, it could forget the customer’s previous calls and repeat questions. With context, it could access structured history data and personalise its advice. In both cases, the LLM is the same; the difference is the information architecture around it.

For public‑sector agencies and regulated industries, the stakes are high. Accuracy, explainability and auditability aren’t nice-to-haves; they’re mandatory. Context engineering directly supports these goals. By curating and tagging sources, you know exactly what information the AI saw. By pruning irrelevant data, you reduce the risk of inappropriate disclosure. By constraining outputs to approved formats or templates, you improve consistency and reduce post‑generation editing. And by managing context centrally, you can scale AI services across teams without losing control of quality.

Thinking of context this way also reframes how organisations should invest. It’s tempting to chase the next big model with a larger context window. But a larger context window without structure is like giving someone a bigger desk without any filing system; the clutter simply spreads further. A smaller model with well-engineered context can outperform a larger one with poor context. This has practical implications for cost, latency and privacy. Instead of streaming vast amounts of sensitive data into a black‑box model, you can provide only the essential curated context needed to complete the task.

Next steps in context engineering

So what should leaders and practitioners do next? Start by mapping your context landscape. What information does your AI need to do its job? Where does that information live? How can it be structured, tagged and retrieved? Then design your pipelines. Treat your context files, taxonomies, tools and style guides as part of your AI infrastructure, not as an afterthought.

Pilot a small use case where you can measure the difference context makes. Track not only the AI’s performance, but also the downstream effects — less manual correction, fewer hallucinations, faster approvals. Build your “memory architecture” before you scale.

Context engineering is still an emerging discipline, but its principles are intuitive: just as you wouldn’t hire a new staff member and give them no training or reference materials, you shouldn’t deploy an AI without engineering the context it needs. In the age of generative AI, context is king, and those who recognise this will lead in crafting digital experiences that are both intelligent and intentional.

If you're interested in applying these ideas to real implementations, view our insight on Drupal’s new Context Control Centre module and how it operationalises these principles.